Unmeek debuted in 2018 under Vlacksquad Records with the single ‘First Time’ and recently released the singles ‘Sorry’ and ‘W.Y.W.S’. Unmeek composes his own music by combining elements of various genres and he plans to continue to push the boundaries of genres to give us a new taste of music. We sat down with the up-and-coming artist in his studio and got to know more about his music style, upcoming projects, and what we can expect from him as an artist.

Enthusiastic Ambition: An Interview with Core.Low

One of the more satisfying aspects of what I do is being able to talk to an artist just as he’s getting his feet wet in the industry. Oftentimes, there’s a bit of reluctance to be too forward or open. They are, after all, just now stepping into an industry that can be quite unforgiving to those who make a little too much noise. However, many artists are just eager to get themselves heard. More, still, are willing to open themselves up to scrutiny for the sake of appealing to an audience who really doesn’t know who they are. Thus is the case with Core.Low. This young man has a heart for his music that is obvious in the way he talks about it and himself as an artist.

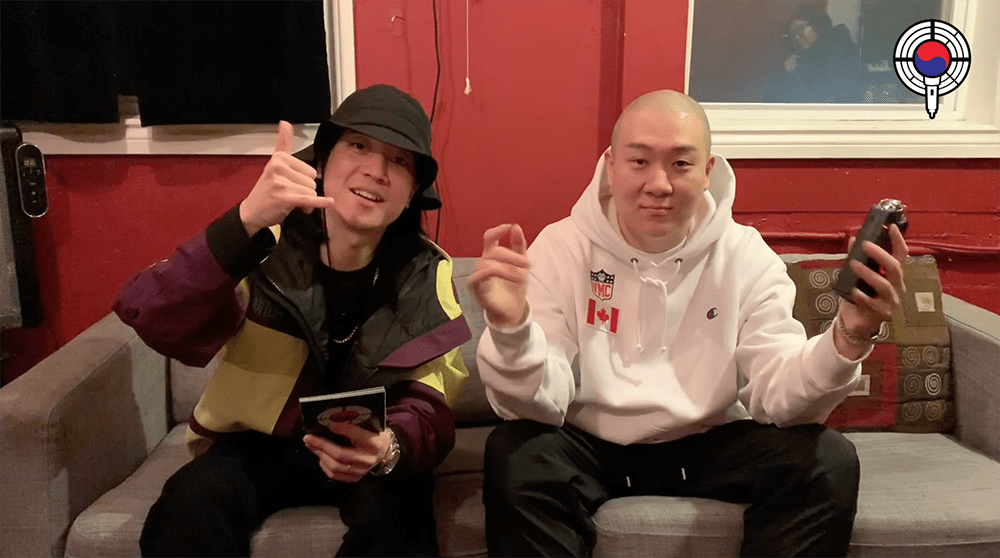

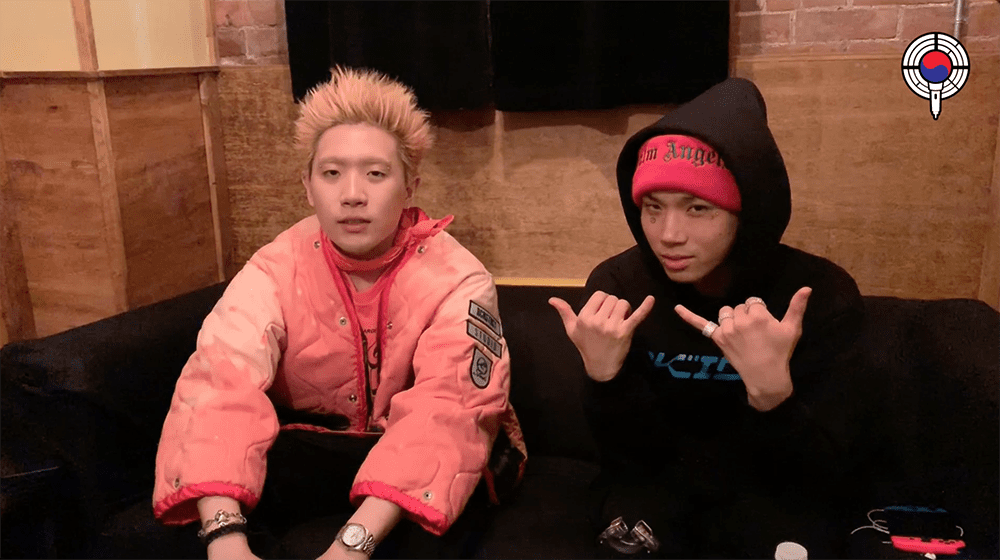

nafla & Loopy Interview (Stage Session Vol.1)

HiphopKR sits down with MKIT RAIN members nafla and Loopy before their performance at “STAGE SESSION VOL. 1” in Toronto. The duo talk about their tour experience, SMTM777, and more.

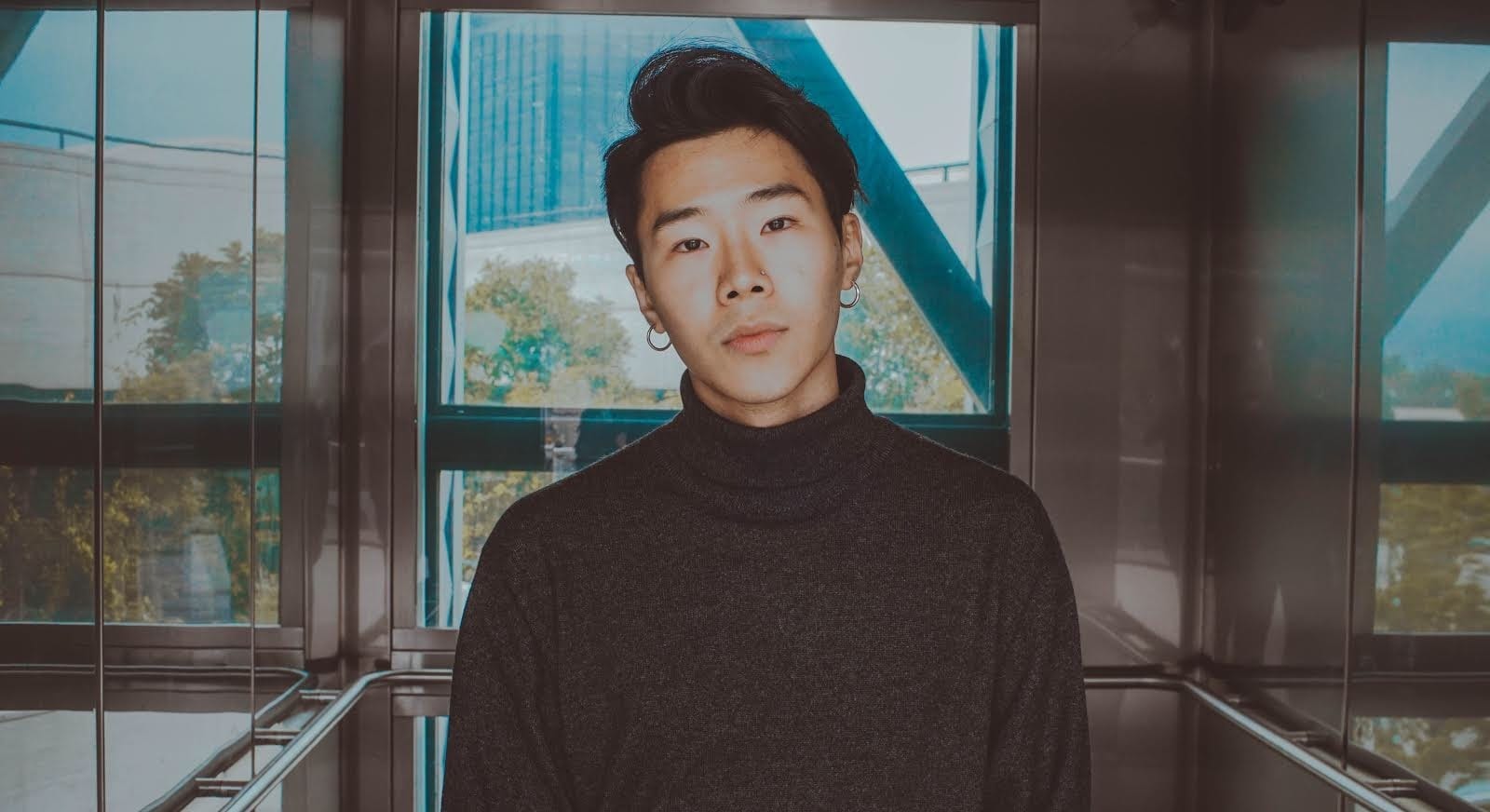

Destined for Greatness: An Interview with R&B Artist JUNNY

In the middle of his recent move to Korea, Korean-Canadian R&B artist JUNNY took time to chat about his goals, dreams, and his creative process.

The World is Yours: An Interview with R&B Artist Babylon

R&B artist Babylon is a simple man with a natural knack for storytelling. While promoting his first LP, “Caelo,” he took time to answer some questions.

“My Journey Has Just Started”: An Interview with Rheehab

While in Seoul, I got the honor to talk to R&B artist Rheehab. We discuss his past, his present, and his desires for the future.

No Such Thing As Perfect Music: An Interview with Amismyk

Those who know my musical obsessions know that I’ve a special place in my heart for one Sima Kim. His is a name that may

The Importance of Honesty in Hip-Hop: A SXSW Interview with pH-1

Hip-hop artist Harry Park, known by the stage name pH-1, gave HiphopKR a very special opportunity. In this in-depth interview, he opened up to us about his faith, his music, and his thoughts on the state of hip-hop in Korea. His honesty was truly a revelation.

2018 is my year! Interview with indie hip-hop artist LATE LEE

Joe Lee, known more commonly as LATE, has been making music for the past few years, doing the work to shape what’s become a signature genre-bending blend of lo-fi, indie, and hip-hop. We took some time to catch up and explore his plans for the future.